It was a cold morning in Dolakha, Nepal. Yagya Kumar Pradhan had just woken up and gone to the nearby pond to wash his face. One of his family members came running to him with a look of fear and sorrow. He waved hastily to him and asked him to come home immediately. Yagya rushed back to find the door to the temple left ajar. Some of the statues inside had fallen on the floor, and their arms / legs had been broken. Yagya was most saddened to find two masks stolen. These masks were sacred to him and his community. These were ‘Bhairav’ masks. Yagya was the head priest of his clan and local community members would often pray to these masks during festivals. The masks had been with his family from the 16th century, for over 500 years. Now they were gone and the temple felt empty without it. Yagya was sure that whoever had stolen the mask had done so, not to pray to it. It would simply end up as part of a fancy art collection of someone rich, or, on the walls of a museum someplace.

Which is exactly what happened over the next 30 years. The masks traveled far and wide, until they were returned to Yagya. This story has a happy ending :)

This week’s post is based on this news story reported in the Himayalan Times about what happened to the masks and how they came back to Yagya. Included here are details based on an interview of Yagya and the art detective by NPR. I have taken the liberty to narrate it with an aim to help my curious audience understand ‘the world of museums and stolen artifacts’.

If you enjoy writing or spinning stories in your head, I conduct a writing course that is designed for young children (8-15) to write beautifully and consistently. If you like the idea of publishing your own book, or playing story-building games with me while I somehow manage the participants to write a page or two each day, join this course. It’ll be fun - that I promise!

How does a Bhairav mask look like?

Tell me a little more about them

Bhairav is a form of Lord Shiva and is worshipped both by the Hindus and the Buddhists residing in Nepal. For the Hindus, Bhairav is considered an incarnation of Shiva and helps his disciples destroy fear. For the Buddhists, Bhairav is a deity who helps his disciples meditate and overcome greed. These masks are often coated in copper, have bulging eyes and snakes engraved on them.

Yagya, when he was a kid used to be terrified of the masks. He wouldn’t dare look at them directly but hang around behind some adults, when it was time to pray.

Back to our story…

Yagya called the Nepali police and registered a case against the lost masks. Luckily, they had plenty of photographs of the masks taken during festivals. They added these to their police report. Unluckily, the police’s search yielded no further results. Yagya thought it was a lost case and that he would never see them again. This was in the 1990s.

A few decades later, one of his cousins got in touch with a group called ‘Lost Arts of Nepal’. This group was active on social media and tried its best to track artifacts that had been stolen from Nepal and had ended up in different parts of the world. Yagya’s cousin sent them a few photos of the Bhairav masks. The ‘Lost Arts of Nepal’ reposted the photos on their social media handle and tagged a few amateur art detectives from around the world.

One such art detective who was tagged was Erin Thompson. She was standing in her kitchen in New York (USA) and making her breakfast. While her bagel was heating, she saw a notification on her phone with the photos of the Bhairav masks. These photos reminded Erin of one of her recent trips to the Rubin Museum in New York. This museum had a special gallery of Nepalese art and right there in the middle of the gallery, she remembered seeing a Bhairav mask! The mask displayed there was one of the main attractions of the gallery.

Erin decided to make a trip to the museum once more to confirm if her suspicions were right. She entered the museum pretending to be a regular tourist and took a few innocent photos of other art works. Once she reached the Nepali gallery, she tried to duck and weave amongst the art pieces there, so she could take photos of the mask from the exact same angle as the original photos had been taken. Comparing these two, she judged that the masks were the same. Eureka! First part of the puzzle had been solved.

Now what? What do you do with just photos of the mask?

Erin had had experience of locating stolen art pieces in the past. She knew that she could walk upto the museum director of Rubin museum and tell them ‘Hi there! This mask you have with you here, was stolen from Nepal. I have some photos on my social media handle to prove it. Could you please send it back?’. One of two things were likely.

(a) The museum director would immediately feel sorry for what had happened, call the Nepali government, and apologise profusely to them. Then he would wrap the mask carefully and courier it to Yagya Kumar Pradhan, residing in Dolakha, Nepal.

OR

(b) The museum director would have Erin thrown out of the museum with a warning to never again set foot inside.

You can guess which was more likely to have happened to Erin, if she had approached the museum’s authorities. As it transpired, Erin did not tell the Rubin museum anything about this, just yet. She decided to collect more information and get it to the New York Police Department, which had a separate cell called ‘Antiquities Trafficking Unit’. She had to prove to them that this mask had been stolen and not legally traded.

‘Antiquities trafficking’ means stealing or looting a culturally significant item, and selling them.

How do you prove that an art item had been stolen

Any art piece that is sold or bought has a paper trail showing the previous owners of the item. This proves that the art has not been stolen, but has been sold by the previous owners willingly.

When Erin set out to trace this mask, she found that

A) it had been bought by the museum from a private art collector who had had it with him for a few years.

B) The private art collector had bought this at an auction held by a very famous auction house called Sotheby’s (in the UK).

C) Sotheby’s had got this mask from a private collector in Hong Kong.

Erin scoured photos online and found that a mask similar to this was at a museum in Dallas (USA).

Erin traced the paper work of the second mask.

A) The Dallas museum had acquired this mask at an auction held by Christie’s.

B) Christie’s had got it from a private collector in Hong Kong.

All trails led to Hong Kong. Papers showed that these masks had been held by a collector in Hong Kong since before 1956. Hong Kong, it appeared, was a place where it was easy for art traders to create false ownership papers for plenty of artifacts. It was hard for anyone to prove that the papers were false.

How was Erin to prove that the masks had been stolen, and not held by a private collector in Hong Kong.

A Nepali law came to Erin’s rescue

Many years ago, after British rule ended, Nepal opened its borders to foreigners to visit its country. Westerners were mesmerised by Eastern spirituality. They loved the tranquility of the monasteries, the beauty of the art work and the meditative properties of some of the sculptures kept in shrines. They yearned for some of these pieces of art to be brought to their homes. Soon, Nepal saw small statues disappearing from its monasteries and temples. These were often legally sold to the westerners.

But the Nepali government was concerned about its heritage and culture rapidly losing shine if its artifacts were taken away from places of worship or homes. So, in an effort to protect its heritage and culture, the country banned export of such items, unless expressly permitted by the government. A law to this effect was enacted in 1956, called the Ancient Monument Preservation Act.

All traders and museum owners know about this law. This is why every trader who creates a false paper trail for any stolen Nepali art will show that the art piece had left Nepal before 1956 and had landed in Hong Kong (or anywhere else). Museums also know this, but as in most cases, don’t care to check the authenticity of the paperwork. After all, they are thrilled to have something fascinating to show their tourists and earn their daily ticket sales.

However, in the case of the two masks, the paper trail had a problem.

The case of the police complaint

Erin had proof to show that the ownership paper of the Hong Kong collector was false. Yagya Kumar Pradhan had filed a police complaint in the 1990s, after the two masks had gone missing. Yagya had carefully kept the copy of his complaint with him for over 30 years.

Erin’s information loop and proof was complete. She sent the paperwork (along with a copy of the complaint from Yagya) to the New York District Attorney’s office. The case of the stolen masks was re-opened. They were able to establish that the masks had been stolen and the museums (Rubin museum in New York and the one in Dallas) were asked to return their respective masks. In a grand repatriation ceremony held in Dec 2023 in New York, the masks were handed back to the Nepali authorities. From there, they were flown to the home of Yagya. He was shocked and thrilled in equal parts that the masks - had made their way home.

There are hundreds of such pieces of art that are yet to return to Nepal

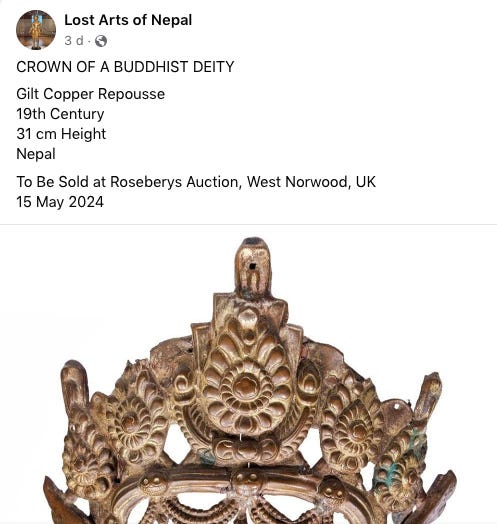

For example, the Lost Arts of Nepal recently posted about this item that was looted from the country and would soon be auctioned in the UK. Hopefully someone like Erin can help it find its way home, by tracking its ownership details and proving that it was stolen.

If you would like a break from reading, I’ve got a delightful podcast to lead you to. Recently, the UK decided that it did not want any immigrants coming into its country without its permission. Especially if they were fleeing war zones or places with no food, the UK has decided to turn these people away. What crazy idea does the UK have now? Is this fair? A teenager joins me to share what she thinks of the UK.